Bethel Temple (Crystal Pool) – 3/13 Marr & Colton

Seattle, Washington

2021-2033 2nd Ave at Lenora

Organ installation timeframe: 1944 – 2003

Back to the Northwest Theatre Organ History: Other Installations page

Bethel Temple Marr & Colton console, c.1998

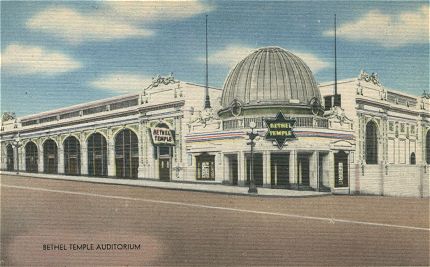

The Bethel Temple church opened in 1944 at the site of the old Crystal Pool Natatorium at 2nd & Lenora. The Crystal Pool was built in 1914 and featured an indoor, heated salt water swimming pool.

The Crystal Pool building was designed by B. Marcus Priteca. The later (1916) Coliseum Theatre building is said to have been inspired by the Crystal Pool.

According to historian Larry Kreisman: “Both buildings had high-relief, neoclassical facades fashioned of glazed terra cotta and corner entries with domes (now missing from both buildings). The Crystal became one of the most popular recreation spots in the city. The swimming pool was spanned by enormous arched steel trusses supporting a glass roof. Surrounding the pool were tiers of seats for as many as 1,500 spectators. Salt water for the pool was piped from Elliott Bay and heated, filtered and chlorinated. Enormous iron boilers located in the building’s basement heated the water. The principal exterior change has been replacement of the entrance pavilion. Modifications have been made to the interior for an assembly space but the building still has the pool’s tile edging and its bleachers. A developer plans to demolish the building and build a condominium tower. The church ownership places the building outside city Landmarks Board jurisdiction.”

In the 1940’s a 3/12 Marr & Colton theatre pipe organ from Indiana was installed by the church. Spokane organ technician George Graham was involved in the install and maintenance.

The organ’s original theatre home is unknown, but several of the console parts and chests were marked with “Indianapolis.”

Although not playable in recent years, the organ remained in the building until 2003 when it was removed by Tedde Gibson and helpers. The Crystal Pool building was be demolished to make way for a new highrise condominium tower. Preservationists were unable to save the building, but the elaborate terra cotta facade on the north and east sides of the building will be retained. The project will also include a domed entrance canopy similar to the original.

Bethel Temple sanctuary showing neon from the 1940’s (see postcard below)

Bethel Temple pipe chamber during removal, May 2003

Bethel Temple pipe chamber showing: French Horn, Clarinet, Vox, Tibia, Diapason, string, Tuba

Bethel Temple pipe chamber showing large offset ranks

Marimba/Harp, Xylophone and Glockenspiel during removal, May 2003

Bethel Temple Kinetic blower (7.5 HP) and generator

Chandelier in the basement level of Bethel Temple. It is not known if this fixture is from the original Crystal Pool or another venue.

Postcard view across 2nd and Lenora, date unknown

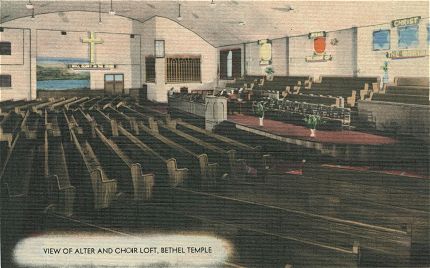

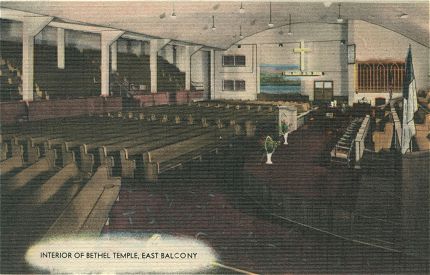

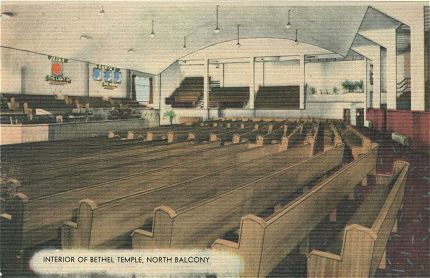

Bethel Temple sanctuary, organ grille visible to left of altar

Patrons swimming at Crystal Pool, date unknown

Crystal Pool entrance, date unknown

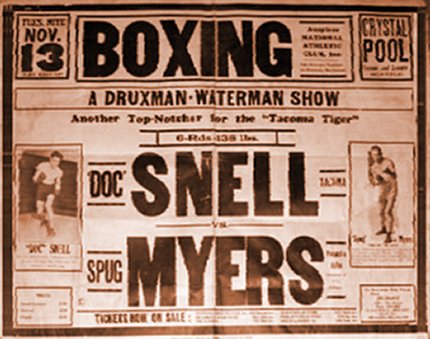

A poster from 1928.

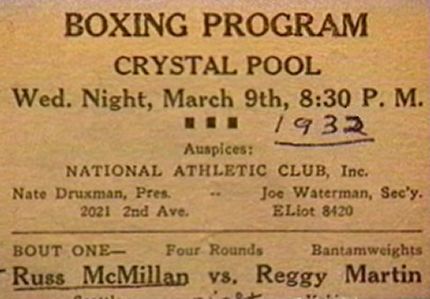

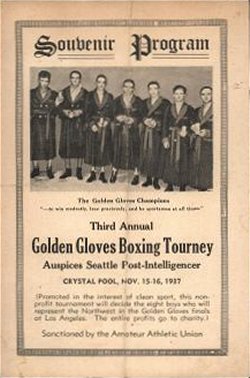

In the late 1920’s, the pool was converted for use as a boxing venue and also saw use as a skating rink in the late 1930’s.

An ad from 1937

Beth Temple building just prior to demolition, May 2003. Note special bracing to allow terra cotta facade to be preserved during the demolition and construction work.

Demolition work, June 2003

These signs were revealed during demolition. It is believed they were painted before construction of the Crystal Pool building in 1914. Photo: Greg Gilbert, Seattle Times

Additional Note:

After Bethel Temple was demolished in 2003, a 23-story condominium was constructed on the site, leaving only the historic terra cotta walls of the original structure. From the website of designers and architects Weber & Thompson come the following description and pictures of what is now the Cristalla Condominium at 2033 2nd Avenue in downtown Seattle. No mention that the building was used as a major downtown Seattle church for over 60 years is mentioned.

Honoring the history of the existing Crystal Pool – an Italian Renaissance building built in 1906 – and respecting the context of the Belltown neighborhood were the two driving forces in the design of Cristalla, a 23-story, high-rise condominium-retail project in the Belltown neighborhood of Seattle. Weber Thompson’s strong design has been commended for its sensitive integration of the original building’s elaborate terra cotta façade. A pergola-like facsimile of the building’s original dome anchors the building’s striking structural composition of alternating layers of glass. (Source:) http://www.weberthompson.com/cristalla.html

Seattle Times articles:

Nov 22, 1999 Battle over Seattle’s Bethel Temple is a question of values

Nov 24, 1999 City should not forget fun times at the Crystal

Dec 16, 1999 Crystal Pool: a unique part of our past

Oct 25, 2000 Tower plans raise residents’ concerns

Seattle Times – Local News: Monday, November 22, 1999

Battle over Seattle’s Bethel Temple is a question of values

by J. Martin McOmber

Seattle Times staff reporter

Belltown has lost its share of old buildings during the construction frenzy reshaping Seattle’s fastest-growing downtown neighborhood.

But the threatened demise of Bethel Temple to make room for condominiums has put a new twist in the battle between preservationists and developers.

It’s a story about God, history, law and what has turned out to be an almighty right to make a dollar – especially if it is the church. It ends with the city’s powerful Landmarks Preservation Board finding itself, in this case, absolutely powerless.

Along the way, it raises a question of what’s more valuable to the soul of a city: good deeds or good architecture?

Bethel Temple, on the corner of Second Avenue and Lenora Street, meets all the criteria for a historic landmark. It’s a one-of-a-kind building by a famous designer that sits in the middle of a neighborhood losing much of its architectural heritage.

But to Bethel Christian Ministries, which serves the city’s poor and homeless and has been a fixture of Belltown for 50 years, a lucrative development deal promises to deliver it from years of financial hardship.

At first blush, it seems a simple debate.

Developer Murray Franklyn wants to demolish all but the two-story facade of the ornate 1915 terra-cotta building, once home to the saltwater bath of the Seattle Natatorium, popularly known as the Crystal Pool.

The neighborhood has mostly been up in arms over the hulking size of the proposed 24-story condominium tower, arguing that the building is out of scale with its surroundings even if it meets zoning regulations.

But for many of those in love with Seattle’s past, Bethel Temple is a architectural pearl the city ought to consider saving.

In its heyday, the Italian Renaissance-style building with its painted green dolphins and regal dome was one of the most popular recreation spots in the city. Under an arching glass ceiling, swimmers splashed in a 260,000-gallon heated pool of saltwater piped in from Elliott Bay, surrounded by decorative tiles and seating for 1,500.

Designed by B. Marcus Priteca, who also gave Seattle its Coliseum Theatre, the Crystal Pool was considered one of the best natatoriums on the West Coast.

“This is a unique building type; there is no other in Seattle,” said Larry Kreisman, the Landmarks Preservation Board’s historian. “It is a part of the collective memory of the city, how it functioned, how we lived, how we worked and how we recreated.”

That’s not so apparent today.

Crystal Pool closed in the late 1930s and since 1944 the building has been home to Bethel Ministries, which long ago did away with the domed entrance and turned the pool into pews. But enough of the old structure remains to have made it a Belltown treasure.

It is also pretty much the church’s only asset. Old buildings aren’t cheap, and the cost of maintaining this one has squeezed the 180-member congregation, Pastor Dan Peterson said.

He said the building is valued at $3 million, and that the opportunity to capitalize on that became too powerful to ignore.

Bethel is not a wealthy church. It appeals more to Millionair Club types than the country-club crowd. Without the influx of cash – and quickly – Peterson said the church would have a hard time continuing programs to feed and help the city’s poor and homeless.

The church might move, but Peterson hopes to find space in the new tower.

“This (building) is a gift passed down through generation to generation,” he said. “The ultimate goal is to balance what can be done to preserve the building. But we want to see lives change; that is our main focus.”

Enter the developer and the lawyers.

Bethel turned to a Bellevue development firm, Murray Franklyn, which is completing work on another condominium/historic-facade project at Belltown’s old Austin Bell building.

In September, the company and church nominated Bethel Temple for landmark preservation, hoping the board would protect the walls on Second Avenue and on Lenora Street and leave the rest of the building available to the wrecking ball.

The firm was hoping for a quick, straightforward decision. It wanted nothing to delay approval of the building permits.

But after a tour of Bethel Temple last week, at least one Landmarks Board member, Kreisman, began asking whether the entire building, not just two exterior walls, should be protected.

That was enough to spook the church and developer, which quickly moved to rescind the application, believing that protecting the whole building essentially would have stopped the condominium proposal.

“It would have created great uncertainty,” said George Kresovich, an attorney for Murray Franklyn. “More importantly, it would almost certainly take a lot of time to get through that process.

“Time is always an issue to a development, and in this case, time was very limited for the church.”

Landmarks Board member Ethan Raup called it “the most offensive display of strong-arm tactics by a developer” he has ever seen.

Normally, a property owner doesn’t have the power to quash an application once the process has started. But on Wednesday, the Landmarks Board was told that under the state constitution, the city can’t designate a church as a historic landmark without the church’s consent.

In a 1997 lawsuit between the city and downtown’s First Methodist Church, the state Supreme Court, citing separation of church and state, ruled the city couldn’t protect a property that a church intended to sell to a private party. Encumbering a building with such restrictions would reduce its value and infringe on the church’s right to make best use of its resources, the court ruled.

“If they decided their religion or mission is served by selling the property and setting up a church in Bellevue, they are entitled to do that, even if it results in the demolition of a historic structure,” Assistant City Attorney Robert Tobin said.

The withdrawal of the landmark application has left the city with few options. Two public meetings on the design review have been held, and the developer is waiting for a final decision from the Department of Design Construction and Land Use.

The Landmarks Preservation Board no longer has any say on what will be saved and what will be preserved.

Copyright c 1999 The Seattle Times Company

Seattle Times – Editorials & Opinion: Wednesday, November 24, 1999

City should not forget fun times at the Crystal

Editorial

HISTORICALLY important buildings often make a poor case for themselves.

The Crystal Pool building in the Denny Regrade has lost its domed entrance, original ceiling and walls, and some of its terra cotta exterior. The pool remains, but filled and covered after the building became a church in 1943.

The building at Second Avenue and Lenora Street looks worn out, nothing like the pleasure palace built by timber baron C.D. Stimson and architect Marcus Priteca in 1916.

Hard to believe now, but Bethel Temple used to be one of the city’s most popular gathering places, an entertainment twin to that other Stimson-Priteca collaboration, the magnificent Coliseum Theater. The Crystal may be the last natatorium in the Northwest.

As a theater, the Coliseum is gone, but the glory it presented to the street was preserved in the renovation for Banana Republic. The Crystal retains much of its exuberant exterior, including carved mermaids and dolphins, but the building faces a wrecking ball to make way for a 23-story condominium building.

Can it be saved? How much is worth saving?

The answers are complex because the owner is needy, the building is significantly altered, and government’s role is limited. The owner, Bethel Christian Ministries, has agreed to sell the building to developer Murray Franklyn, hoping to raise money for its service to the poor and the homeless.

Murray Franklyn was willing to preserve some of the two-story facade, but its plans for the condo tower make the creamy terra cotta look like material slapped on unwelcoming walls.

Murray Franklyn recently withdrew its application to the city’s Landmark Preservation Board when board members inspected the building and wondered if at least some of the interior should be preserved. The developer feared rising costs, unworkable suggestions and delays.

City policies encourage residential projects in the regrade, but also encourage preservation of significant buildings. As landmark board member Larry Kreisman points out, old buildings tell stories. As an artifact left from a significant age, the Crystal tells how people had fun in the 1920s and 1930s. There’s value in the memory of a young grandpa snapping towels at his chums and checking out the Flappers.

What can be done? The city has limited authority because the building is owned by a church, but it can play a constructive role.

City officials should encourage the parties to re-examine the design and strengthen the proposed tower’s sense of history. The developer may not have to do it, but should do it. Fine urban design treasures the past.

Copyright c 1999 The Seattle Times Company

Seattle Times – Editorials & Opinion: Thursday, December 16, 1999

Crystal Pool: a unique part of our past

by Larry Kreisman

Special to The Times

I am reminded of the story of the blind men who grab hold of different parts of an elephant and try to describe the beast. The owners of Bethel Temple and its future developers argue that the Crystal Pool at Second Avenue and Lenora Street has undergone a number of significant alterations that call into question its integrity and historic value. Others find that, despite these alterations, all the clues to its former use are there to be seen and experienced – the terra cotta facades, the bleachers, the tile pool edging, the wooden floors and doors leading to the dressing rooms, the original chandelier that hung in the entry rotunda, and the structural columns and spans that are boxed in and hidden but intact. The original boiler equipment, manufactured by “The Natatorium Company,” and the original ventilating system, manufactured by Western Blower Company of Seattle, are also intact.

On Nov. 17, the Seattle Landmarks Preservation Board was prevented from discussing the building’s integrity or its ability to convey its significance because Bethel Christian Ministries, the owner, withdrew it from landmarks consideration at a designation hearing. Ironically, they had nominated the building only a few weeks earlier.

But Crystal Pool deserves discussion because it is a significant piece of public history that belongs to all of us who reside in Seattle. The building’s polychrome terra cotta facades are decorated with dolphins and tridents that were visual clues to the building’s purpose. Its structure was developed to allow for uninterrupted open space; enormous arched steel trusses supporting a glass roof spanned the pool. Surrounding the pool were tiers of seats for as many as 1,500 spectators. It had salt water piped direct from Elliott Bay, heated, filtered, and chlorinated.

The pool was a major investment by C.D. Stimson, one of the city’s prominent businessmen, in providing Seattle with a first-class recreational facility that was a model of its type. For its architect, B. Marcus Priteca, it and the Coliseum Theatre, designed at the same time, were prototypes for significant entertainment palaces for Alexander Pantages plus the Warner and Orpheum theater chains.

There may be disagreements over the building’s integrity at this point in time, but there can be no question that it has the ability to convey its significance, and that all the clues to its original use are in place, even with alterations, with the exception of its entrance rotunda. Even in that case, one can climb stairs in the bleachers leading to corridors that led into the dome of the rotunda.

We are in a particularly active growth period that will continue to affect existing buildings that were important in shaping downtown and neighborhood character. The Landmarks process is not going to solve those problems. Nor should it be the place for it.

The city really needs to stand behind and support the cultural resources it discusses in the Comprehensive Plan with some concrete efforts. It gives lip service to the importance of historic preservation and historic-built resources in defining and enlivening communities and encourages neighborhoods to do strategic planning that may include these. But it also encourages development that endangers the same resources that it should be protecting – not through the landmark process, but by a more careful and long-sighted approach to development.

Not every building should be a landmark, but many are certainly significant to the community and should be protected simply because they are valuable physical definers of place. Fortunately, developers of projects that affect potentially eligible properties do have to bring these properties before the board for review.

Why does the Crystal Pool hold importance to the city? In previous Seattle Landmarks Board hearings, it has been possible to bring in examples of other buildings of a particular type that still exist in the city as a basis for comparison. We cannot do that with the Crystal Pool for the simple reason that it is unique in Seattle. This kind of pool was a popular recreational feature in any major city early in the century.

The Crystal, because of its size, its filtered saltwater and its convenient downtown location, became one of the most popular spots in the city. While it has not operated since the 1940s, it still evokes vivid memories for generations of senior Seattle residents. Consequently, its social and cultural value is equally as important as its architectural presence.

Since the proposed development would preserve only the outer walls, the integrity of building and interior space, which is integrally related, will be totally lost. For comparison – and to think about how such a building could be refurbished to allow experience of its interior spaces – one can visit the Crystal Pool in Victoria, B.C.

Because it is unique, because there are no others like it anywhere in the Seattle area that we know of, its integrity and continuing use are less an issue than the fact that it exists to tell its story. Current zoning may allow commercial and multifamily housing of many floors on the site. But it is also possible to redevelop Crystal Pool in the same way as developers in Spokane recently redeveloped their historic downtown steam plant into meeting space and retail space. The project gives visitors an opportunity to experience and understand the workings of this important industrial building, including its coal bins, chimney stacks, and steam-generating equipment.

For that matter, The Coliseum Theatre, despite the replacement of its rotunda and some major alterations to its interior, was designated a Seattle landmark in its entirety. Banana Republic architects worked with the Landmarks Board to develop a different use for it while preserving its ceiling, balcony and proscenium with an eye to a potential return to its original use.

In adaptive reuse terms, the Crystal Pool is a gem of an opportunity waiting to happen – not an obsolete and useless building sitting on a million dollars of developable real estate.

Lawrence Kreisman is program director of Historic Seattle and director of the Viewpoints tour program for the Seattle Architectural Foundation. He serves as historian on the Seattle Landmarks Preservation Board and is author of “Made to Last: Historic Preservation in Seattle and King County.”

Copyright c 1999 The Seattle Times Company

Seattle Times – Local News: Wednesday, October 25, 2000

Tower plans raise residents’ concerns

By Brier Dudley

Seattle Times staff reporter

Seattle city planners have agreed to let a developer raze the former Crystal Pool in Belltown to make way for a 24-story office and condominium tower.

From 1915 to the 1930s the pool made Belltown a playground for earlier generations, who swam beneath its glass roof in saltwater pumped up from Elliott Bay.

Last year historians attempted to save the building at Second Avenue and Lenora Street but only the ornate, nautical-themed terra cotta facade will remain.

The project sidestepped preservation rules because the building is currently used as a church (Bethel Temple) and recent court rulings limit governments’ control over church buildings.

But the project isn’t home free. Residents of nearby condos said yesterday they might appeal the city’s Oct. 19 approval, in part because they think the new tower is too big for the neighborhood.

That could open a new front of residential land-use battles. Traditionally it’s residents in older neighborhoods of single-family homes who fear high-density housing developments will ruin their neighborhood, not high-rise dwellers concerned about the new tower going up around the corner.

“I think it’s kind of ridiculous not-in-my-backyard,” said Steve Washburn, project manager for Bellevue developer Murray Franklin.

Washburn said an appeal would delay the building, now scheduled to open by summer 2003, and it has already been redesigned to appease neighbors.

Likely to appeal is retired Boeing engineer John Pehrson and other residents of a 26-story condo tower on the same block.

The new tower would block some views of the Cascades but Pehrson said residents were more concerned about its design and effect on traffic.

“Our concern has been the massiveness of this building and how it fills the whole lot almost, compared to everything else in our community,” Pehrson said.

Over a dozen residents of Pehrson’s building, at 2000 First Ave., sent the city letters opposing the project. Among them were a developer, the chief brain surgeon at Swedish Medical Center and former University of Washington president, William Gerberding.

“We believe the density of downtown Seattle has reached a level that now impinges on the quality of living for existing downtown residents,” neurosurgeon Allen Wyler wrote the city last year.

City planner Vince Lyons said residents should brace themselves for even more high-rises in the neighborhood.

The Second and Lenora tower is one of six planned for the “downtown mixed commercial” zone encircling the central office and shopping districts.

“Hey, we’ve had to look at that building for the last 15 years,” he said of Pehrson’s building. “Now you’re going to see more of an infilling around the retail core, and around the office core . . . because it’s available property and a hot market.”

Lyons said feedback from neighbors and the city-design process helped produce what may be one of the city’s more distinctive residential towers. It will resemble newer towers in Vancouver, B.C., and San Francisco, that are mostly glass on the upper stories, as opposed to the more common Seattle towers that are mostly concrete.

At the corner of Second and Lenora the building will have a steel pergola reminiscent of the pool’s original domed entrance. The main floor will house a restaurant over underground parking. Above will be four floors of offices, topped with 179 condominiums.

Bethel Temple, a Pentecostal church that has owned the building since the 1940s, will relocate. Inside, the pool was covered years ago and there are no decorations left comparable to the facade.

The church used the gymnasium-like room for a sanctuary and its tiered seats for pews. Under the floor, in the pool basin, is a carpeted room used for concerts and Thanksgiving dinners for the homeless.

On Oct. 19, Lyons approved the project, on condition that Murray Franklin widen an alley, advise residents about commuting options, provide bicycle-storage areas, preserve artist-designed benches along Second and provide an awning along Lenora.

The developer must also refine the building design as suggested by the city Design Review Board. It must add vertical “pinstriping” and change the exterior to create “a visually more slender building.”

Also, the developer must recognize the former natatorium use of the site. “This could be in the form of a well-designed plaque,” the decision said.

Residents may appeal the ruling until Nov. 2.

Architectural historian Lawrence Kreisman, who tried to preserve the entire pool building, said he would not appeal. But he’s glad others might and said it was refreshing that downtown dwellers realize they can have a say in how their city is changing.

“It’s nice these community people are at least looking at what’s happening in their neighborhood. Most people who call me seem so helpless,” he said. “I just have a sense that a lot of people are feeling they don’t have control of their neighborhood anymore, that individual property owners can do what they want.”

Copyright c 2000 The Seattle Times Company

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.